9. "You're on to something big," says Johnny

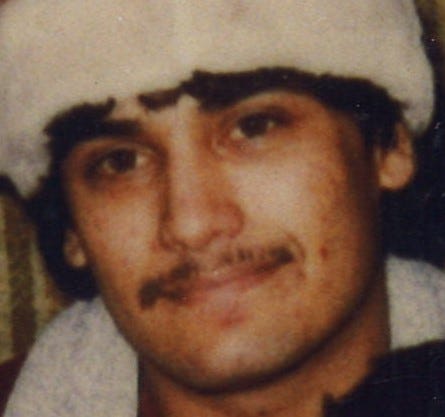

A strange and violent character, this Johnny Crouse. Or maybe disturbed is the best way to put it. A troubled child who started running away from home and stealing cars at the age of eleven, and no wonder.

As a prison counselor noted early on, his parents’ efforts to discipline him usually consisted of tying him to a chair and beating him until he turned blue. No education beyond the ninth grade, no skills. In prison he is a victim of sexual predators.

In 1980 he moves from his hometown in Nebraska to Oregon where he is promptly arrested for two robberies and sentenced to twenty years in the Oregon State Prison. Released after eight, he’s back on the street in Salem a month before the Francke murder, reporting to his parole officer and working at a part time job washing cars.

Crouse’s first story, which he tells his parole office about a month after the murder, is that he saw five Mexicans running away from the Dome Building that night. State police investigators give him a polygraph, say he didn’t kill Michael Francke, and dismiss him as a non-suspect.

A month later he’s back in prison for the knife-point robbery of a woman in a supermarket parking lot – and this time he confesses to having committed the murder himself. What he tells a Justice Department investigator, Randy Martinak – who to this day believes that Crouse is guilty – is that he was able to break into Francke’s car using a coat hanger. Francke surprised him as he was burglarizing the car. They fought when he tried to get away, and he stabbed Francke.

In recorded telephone conversations to his brother and mother in Nebraska the next day, he breaks down and says he committed the murder. Perhaps even more significantly, in his confession to the police, he seems to know things about the murder that haven’t been released to the public, such as the stab wound to Francke’s left bicep.

Plus this intriguing fact – reported also by the maintenance man, Wayne Hunsaker, who saw the two men in front of the Dome Building that night – that the man who turned and ran, disappeared from view behind a big green generator on the state hospital grounds. Crouse says that’s where he ran.

For a while there it looks like the Marion County DA, Dale Penn, and the state police have been right all along. Crouse’s confession exactly fits their theory that the murder was the result of a bungled car burglary.

On the other hand, when investigators ask Crouse to demonstrate how he managed to break into Francke’s car using a coat hanger, he can’t do it. He fails three times.

It’s a serious problem, and one that haunts the case to this day. Crouse was almost certainly there. Whether he was involved in the murder or not, he knows things he couldn’t know otherwise. At the very least, he had to hear them from someone who was.

Then just three months later, Crouse is apparently no longer of interest to the Task Force. It’s all very strange, just on the face of it. But as the records now available make clear, it was even stranger than anyone outside the investigation could have known at the time.

Crouse had been back in prison for two months when Pat Francke, the older of the two brothers, was able to arrange a visit. Crouse tells him he didn’t commit the murder but knows who did, and he says Corrections officials are involved. “You’re on to something big,” he says.

We know this much because Pat tells me about it, and of course I write a column about it. But the rest of the story remains buried for some time in state police reports.

A week later, a police officer takes Crouse, along with Penn and the prisons security chief, Robert Kennicott, for a ride outside the prison. Along the way, Crouse points to a house just a couple of blocks from the Dome Building and says the guy who did it lives over there. The address of the house is 942 Park Avenue, and the person who lives there is an ex-con named Buck Burgess.

It turns out that during the short time he was out of prison, Crouse used to hang out at Buck’s place. But even today, Burgess’s precise connection to the murder remains a troubling mystery.

In fact, Burgess, whose rap sheet includes convictions for the manslaughter of a year-old baby and the rape of two young girls, has already come to the attention of investigators. Just two days after the murder, in fact, he was spotted sitting in his pickup, watching the crime scene investigators at work. He was brought in for a polygraph, which was determined to be inconclusive and then, inexplicably, dropped from consideration.

But the point here is not just that investigators, for whatever reason, had no interest in pursuing Burgess, but that by this time Crouse had completely changed his story and was now implicating Corrections officials.

The same day, the state’s records show, Crouse meets with Penn and Sarah Moore, the deputy DA now in charge of investigation, and tells them he’s innocent but was asked to carry out the murder by two members of the Corrections Department staff.

And at least for the state police and DA’s office, that’s the end of any interest in Johnny Crouse as a suspect in the murder. Who knows whether he’s telling the truth or just jerking everybody’s chain? But the troubling fact remains: He knows things about the murder he shouldn’t know.

In exchange for recanting his previous confession as well as any claims to have personal knowledge of the murder, the DA’s office gives him immunity from hindering prosecution for “any false statements that Mr. Crouse may have made in the course of previous interviews concerning the Michael Francke homicide.”

After six months of watching the investigation going nowhere, Kevin has had enough of being told to keep his mouth shut and trust the investigators to do their job. He gives me the go-ahead and I write a column about his previously off-the-record conversation with Michael about the “organized criminal element” he’d discovered in Corrections.

In the course of his long-distance investigation from Florida, Kevin has also learned that investigators have been showing an artist’s drawing of the Man in the Pinstriped Suit to Dome Building workers. I get a copy and publish it. Since the Man in the Pinstriped Suit was seen in the Dome Building after closing time on the night of the murder, he’s obviously at least a person of interest, yet investigators had still not released the drawing to the public.

The next day Governor Goldschmidt holds a press conference, demanding to know: “Where is this bullshit coming from?” As we’ve already discussed, Goldschmidt is undoubtedly trying to fend off any sort of investigation that might lead to the disclosure – whether by the FBI who might stumble on something, or by state police who might be blackmailing him – of a highly illegal and certainly career-ending sexual relationship he’d had with a 13-year-old girl when he was mayor of Portland. Maybe there’s more to it, but I don’t think so.

And then just a few days later, Penn gives an interview to a dependably compliant reporter at the Oregonian, which appears under the headline: “DA Discounts Corruption.” He denies that Kevin ever told him about an “organized criminal element.” The first he heard about it, he says, was just a few days ago when he read it in the newspaper. Furthermore, he’s quite sure there is no corruption for Francke to have been investigating in the first place.

But what an odd thing for a district attorney to say. To put a point on it, Penn has just called the brother of a murder victim either a liar or just plain crazy, take your pick. And when you stop to think about it, what possible motive would Kevin have for wanting to lead his brother’s murder investigation astray?

Because as we know now, Penn was just flat out lying. He’d been told several times, and not just by Kevin but by state legislator Mike Burton as well, that Francke was indeed about to expose a criminal level of corruption in his department.

And then, of course, there’s Penn’s curious decision to drop Johnny Crouse as a suspect, just as Crouse was starting to talk about connections to Corrections officials.

But it doesn’t stop there.

In July, just a month after Penn and lead prosecutor Sarah Moore have dumped Crouse, the Francke Task Force receives another lead, which they also apparently consider too hot to handle.

What happens is that an inmate named Konrad Garcia tells his counselor that in the fall of 1988, about three months before the murder, he was approached by an up-and-coming Salem gangster named Tim Natividad with a proposition to kill Francke. In exchange, Garcia says, he was assured that he’d be released from prison, which he knew meant that the prison lawyer, Scott McAlister, who also controlled the parole board – and whom Francke had forced out of his job a week before he was murdered – had to be involved.

Now this is probably the last thing the Francke Task Force investigators want to pursue. To the bitter end, Penn will insist that McAlister is not a suspect. However, since the counselor had submitted an official report to their tip line, they at least have to go through the motions and interview Garcia – who, to make matters even more complicated, is a former cell mate of Buck Burgess.

Yes, that’s the same Buck Burgess whose house on 942 Park was pointed out by Johnny Crouse before he was abruptly dropped as a suspect.

So the job falls to state police officer Ken Pecyna, who by time has taken over as lead investigator on the case. And as his brief report on the interview plainly shows, he doesn’t consider Garcia credible or the Natividad angle worth any further consideration.

As for McAlister, his name doesn’t even come up in the interview. Or if he does, Pecyna certainly doesn’t bother to include it in his report.

But what makes this even more intriguing is that this guy, Tim Natividad, who Garcia says asked him to kill Michael Francke, looks very much like the drawing of the Man in the Pinstripe Suit.

Maybe he is and maybe he isn’t. But at least you’ve got to give it a second look, don’t you think?

Maybe it would behoove us to think about how this would have played out if Liz had not shot Natividad. I'm sure that was NOT part of the plan. What would have been Natividad's fate? Liz said he was out of his mind after "he killed a man" (presumably Francke). Maybe Tim got an idea shortly thereafter, that they were going to pin the whole thing on him. How would that have played out? Liz messed up the plan? I think it's why they scrambled to find a patsy, someone who was not part of their gang of thieves, Frank Gable, because Tim's people had little reason to keep the secret once he was dead. Maybe.

I think a higher-up corrections official was calling the shots. McAlister hired Natividad, and Natividad enlisted the help of others vis-a-vis Konrad Garcia's mean culpa to Kevin Francke. McAlister arranged to have the premises ready for the murder along with hiring Natividad. But the problem is, if McAlister told Natividad to make it look like a suicide, why was a knife used? I think a corrections chief had his own personal operative on the plan, someone who was closer to the chief than McAlister, and that person knew the goal was to get his briefcase and/or computer, as well as kill Francke. Maybe the super tall big guy in the trenchcoat? Someone who could subdue Francke while Natividad stabbed him to death?