Some thirty-four years later, it’s still painful for him to think about it. Asking himself over and over again if it would have made any difference if he’d come forward.

And who knows if it’ll make a difference now? The cover-up of the Michael Francke murder seems as firmly in place as ever. But one thing you learn is you can’t worry about what you can’t control. Mike Burton is 82 years old now – time to be tying up all sorts of loose ends – and this is his story:

It was Friday, January 13, 1989, the week before Michael Francke was killed, and the two of them were driving back to Salem after an inspection tour of a couple of prisons in eastern Oregon. The last one being Pendleton, way out by the Idaho border, so it was a one long trip, you’d better believe it. Five hours or so.

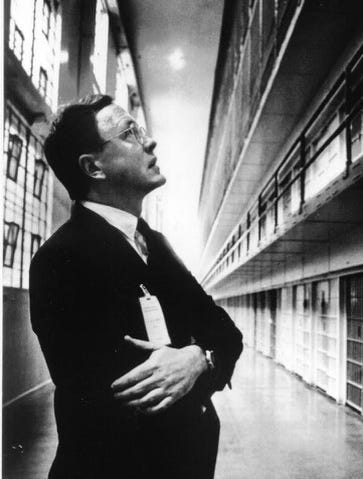

Francke was driving the big state-issue sedan, and Burton, who was then a state legislator from Portland, was sitting across from him in the front seat. He’d been invited along on the trip because he was a member of the governor’s prison reform committee. The other committee members had already arranged for their own transportation home.

It was winter. Snowing along part of the route through the gorge, Burton remembers. Plenty of time to talk, getting to know each other.

Before getting into politics, Burton had served twelve years as an Air Force officer. Although he wasn’t supposed to talk about it, he was still tormented by what he’d seen over there in the country’s secret and illegal war in Laos. Back in the states, after a few years on the Portland area Metro council, he’d run for state office and had been in the legislature almost four years now.

Francke, it turned out, had done time in the military too, as a Navy JAG, or legal officer. Then a stint as a judge in New Mexico before getting into the corrections business, almost by accident it seemed.

After a savage riot in the penitentiary, the New Mexico governor had asked him to take charge of that state’s prison system. Following his success there, he’d been hired as head of the Oregon Corrections department, in May of 1987, by the newly elected governor Neil Goldschmidt, which means he’d been on the job for just over a year-and-a-half.

So there they were, whipping down the highway toward Salem, and at a certain point, after the getting-to-know-you part of the conversation had more or less come to an end, Burton asked about a flattish box-like object on the front seat between them. It wasn’t a briefcase, but what was it?

“It’s a laptop computer,” said Francke.

“No kidding,” said Burton. He’d never seen one before. All he’d ever seen were desktop computers, and he didn’t even have one of those in his office yet.

Laptops were rare birds back then, Burton explains. This one was of course much thicker and bulkier than the slick, present day models, but it still seemed a bit inconceivable they made them so small you could actually carry one around with you.

“Go ahead,” said Francke. “Open it up, but don’t touch anything. I don’t want to lose any information.”

So Burton picked it up and raised the top. It was, he clearly recalls, an NEC, a Japanese model then on the market.

“It’s the latest technology,” said Francke proudly, as he proceeded to hold forth on the technical capacity of his laptop. As it turned out, Francke, who had actually minored in computer science in college, was something of a computer nerd. “It’s going to change the way we take notes,” he said.

After a few more moments of gazing at this marvel of 1980s computer technology, Burton folded it shut. “So what do you use it for?” he said.

“That’s my investigation,” Francke said after a momentary pause – “and it’s all there on the computer.” For the past year, he said, he’d been doing a study of the prison system.

“It’s going to blow the top off everything,” he said. “It’s going to shake things up. There’s a lot more corruption there than you could imagine.”

“Are we talking about prison labor issues here?” asked Burton. At a recent meeting with Francke and some legislators there’d been some discussion about the misuse of prisoners to mow officials’ lawns or work construction jobs for free.

“No,” said Francke, “it’s much more serious, much deeper than that. It’s a financial analysis of the prison system and the books just don’t balance.”

“What I’ve found is an organized criminal effort to defraud the state,” Burton remembers him saying. “There’s corruption all the way through the ranks.”

Looking back, says Burton, the funny thing is that Francke actually seemed more excited about the computer’s capabilities than anything else. “It’ a great tool to have,” he remembers him saying, “and boy, have I got them.”

Burton asked if there would be criminal charges, and Francke said yes.

“Well, can you tell me about it?” asked Burton.

“No,” said Francke, “but you’ll read about it in the papers.” As a matter of fact, he said, he was going to be presenting his findings to the senate Judiciary Committee next week on Wednesday.

It was late, maybe 9 or 10 p.m. that night when Francke dropped Burton off in Salem. Just four days later, shortly after midnight on the morning of January 18, Francke’s body would be found lying on a porch outside the office building where he worked, lying in his own blood and dead of a stab wound to the heart. We don’t know the exact time of death, but it had to be sometime after seven the previous evening because that’s when the meeting let out. He’d been working late, preparing for the legislative hearing the next day.

But that’s not the end of Burton’s story, so sit tight.

After another week went by, and all the official statements coming out of Salem seemed to indicate that the murder was most likely the result of a bungled car burglary, Burton decided he’d better go see Dale Penn, the Marion County DA in charge of the investigation, and tell him what he knew.

And when he’d finished, he says, Penn, who’d been sitting there behind his desk with a sort of stony look on his face, thanked him for his information and said he’d be getting back to him. Which he never did.

And then a few months later, with the media reporting that the investigation had turned toward a small-time drug dealer, Frank Gable, who investigators seemed to believe killed Francke when Francke caught him burglarizing his car, Burton thought he’d try again.

So he placed another call to Penn’s office, and this time he didn’t even get a call back.

“It’s one of the things I regret the most,” he says. “But that’s when I decided there was not much I could do.” It was almost like the secret war in Laos all over again. “All these big time things going on. Something much deeper than I understood. If I held a press conference – and I did think about it for about three minutes – who would even listen to me?”

Well, certainly not the state cops who were busy fabricating a case against a lone car burglar, who would later be completely exonerated by two federal appeals courts after spending thirty years in prison.

And certainly not Dale Penn, the Marion County DA in charge of this dirty investigation, who’d already tried to make Kevin Francke out as crazy for saying that just three weeks before the murder his brother told him he’d discovered an “organized criminal element” in his department and would be “cleaning house”.

And most certainly not the governor, Neil Goldschmidt, who as we now know was secretly maneuvering behind the scenes to keep the FBI out of the Francke investigation.

And who, after a series of columns I’d written for the Oregonian, reporting Kevin’s story about the phone call and raising questions about corruption in the Corrections department, held a press conference to demand: “Where is this bullshit coming from?”

And you wonder why I don’t let this thing go?

That's the big question alright, and I probably should have addressed it above. I haven't been able to find out if it ever turned up. The one person who might know the most about the evidence in the case, the investigator for the federal public defender, says she can't recall ever seeing it among the state's evidence. It was very likely taken that night.

Anyone know what happened to the laptop?