5. "It was supposed to look like a suicide"

So the question is: Whatever happened to the NEC laptop computer lying on the front seat between Michael Francke and Mike Burton?

You know, the one with the investigation that Francke said was going to blow the top off everything?

Well, the person I consider most expert on these matters, the federal public defender’s lead investigator, Wendy Kunkel, says she doesn’t recall seeing the computer among the evidence in this case, which would of course have included Francke’s possessions at the time of his death.

And my other go-to expert on this case, Kevin Francke, who’s devoted the last thirty years of his life to finding who killed his brother, doesn’t know anything about it either. Until Burton came forward, he says, he didn’t even know that Michael had an NEC laptop.

So the only likely explanation, because there’s no reason to doubt Burton’s veracity or his memory on this, is that the computer was taken the night of the murder and probably destroyed. Along, of course, with the discs on which all the information was stored. Which is important to keep in mind because in those days, computers had a very limited memory – 640K for this NEC laptop – and anything of any length at all had to be kept on floppy discs.

Sounds almost like a murder mystery, doesn’t it? That’s because it is.

From the beginning, the big lie coming out of Salem – from the state police, the Marion County DA’s office, as well as the governor’s office – was that Francke couldn’t have been investigating corruption in the Corrections department because there just wasn’t any, and that Kevin was crazy when he said his brother told him he’d discovered an “organized criminal element” in his department and was going to be “cleaning house.”

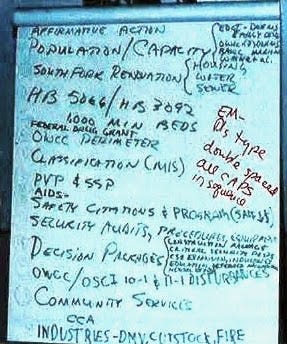

And if Burton’s revelation doesn’t drive a stake through the heart of it, then this Polaroid photo of Francke’s whiteboard – from his staff meeting the night before he was scheduled to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee – should.

It’s a working list of the topics Francke would be discussing the next day. And on the bottom line of the whiteboard – which means it’s the last and most important issue Francke was going to address – is the word FIRE, an obvious reference to the so-called A-Shed fire which had occurred at the prison six months earlier.

On the same line, there’s also the word INDUSTRIES, short for Prison Industries, which controlled the operations of the commercial laundry and furniture factory, as well as the prison’s farm annex, a traditional source of graft and the wholesale theft of animals.

But Prison Industries also had a warehouse, just outside the prison walls, called the A-Shed, which in July 1988 burned to the ground destroying everything in it, including several pieces of heavy equipment – or so Industries declared when they filed an insurance claim for $1.17 million.

As an ombudsman’s investigation two years later would establish beyond doubt, using actual photos of what remained (or in this case didn’t), all the heavy equipment had been sold off at a private auction the month before, and at the time of the fire there was absolutely nothing in the A-Shed but scrap furniture.

It was, in other words, a million-dollar insurance scam. Plus the theft and sale of government property, plus arson and who knows what else. And well before the ombudsman began his investigation – in fact before the ombudsman position had even been created – Francke had gathered all the evidence he needed to prove it.

So if you have any lingering doubts about whether Michael Francke was about to expose an “organized criminal element” in his department, or that his investigation was going to “blow the top off everything,” resulting in the termination of some officials’ careers and sending others to prison, well, we’re probably wasting each other’s time here.

But if you’re willing to entertain the thought that this needs to be treated as an open murder case – which means you’re probably not involved in politics or law enforcement in the state of Oregon – you’d probably want to look at the last person to see Francke alive after that staff meeting broke up the night of the murder, right?

And that, as it turns out, would be Dave Caulley, the fiscal administrator for Corrections, whom Francke had already informed that he was being demoted. Caulley said he saw Francke at about 6:45 in the Dome Building hallway as he was leaving to go home. His car was parked next to Francke’s in the lot out front.

Or the person who finally answered the desperate phone calls to come search for Francke, after a couple of women on their way home from the Dome Building , found Francke’s car door wide open at about 7:05, the car’s dome light blazing away in the night, and Francke nowhere to be seen.

That would be Francke’s assistant director Dick Peterson, to whom Francke had just the day before delivered the same bad news.

Once Peterson got to the Dome Building, he called Caulley to come help him look for Francke. And though they performed what Peterson described as an exhaustive search of the premises, they didn’t find Francke’s body, which was discovered by a security guard about five hours later, at 12:42 a.m., lying on a porch just outside his office.

It was a strange search, to be sure. Caulley said he didn’t even go into Francke’s office to look for him because he was afraid he’d find that Francke had shot himself. To this day, however, there’s absolutely no evidence that Francke was particularly depressed, much less suicidal, and at the time he was obviously looking forward to his testimony the next day before the legislative committee.

And then, of course, there’s the longtime Corrections lawyer, Scott McAlister, on assignment from the AG’s office, who Francke had forced out of government service one week before he was murdered.

Of course, McAlister ended up on his feet with a new prison job in Utah, where he was arrested for the possession of child pornography after an ex-girlfriend tipped off the FBI.

The same girlfriend also related a story about a dinner party one night where she overheard McAlister discussing the Francke murder with another former Oregon prison official. “They fucked up,” she heard McAlister say. “It was supposed to look like a suicide.”

But the really funny thing is that in the course of their year-long investigation, the state police didn’t even bother to interview McAlister.

Kinda makes you wonder, doesn’t it?

Some have been wondering for a long long time. . . . .