10. Frank Gable is the perfect patsy

There is, in fact, reason to believe that the state police started setting up Gable up as early as May of 1989 – which, not too surprisingly, was just about the time they were dropping Johnny Crouse as a suspect and pooh-poohing a report that Tim Natividad had tried to recruit an inmate named Konrad Garcia’s to kill Michael Francke.

And maybe that’s just a big fat coincidence. On the other hand, it’s also pretty obvious that at this point they needed a patsy to prevent the investigation from dragging them into certain sensitive areas – such as who really killed Michael Francke – and Gable was just the ticket.

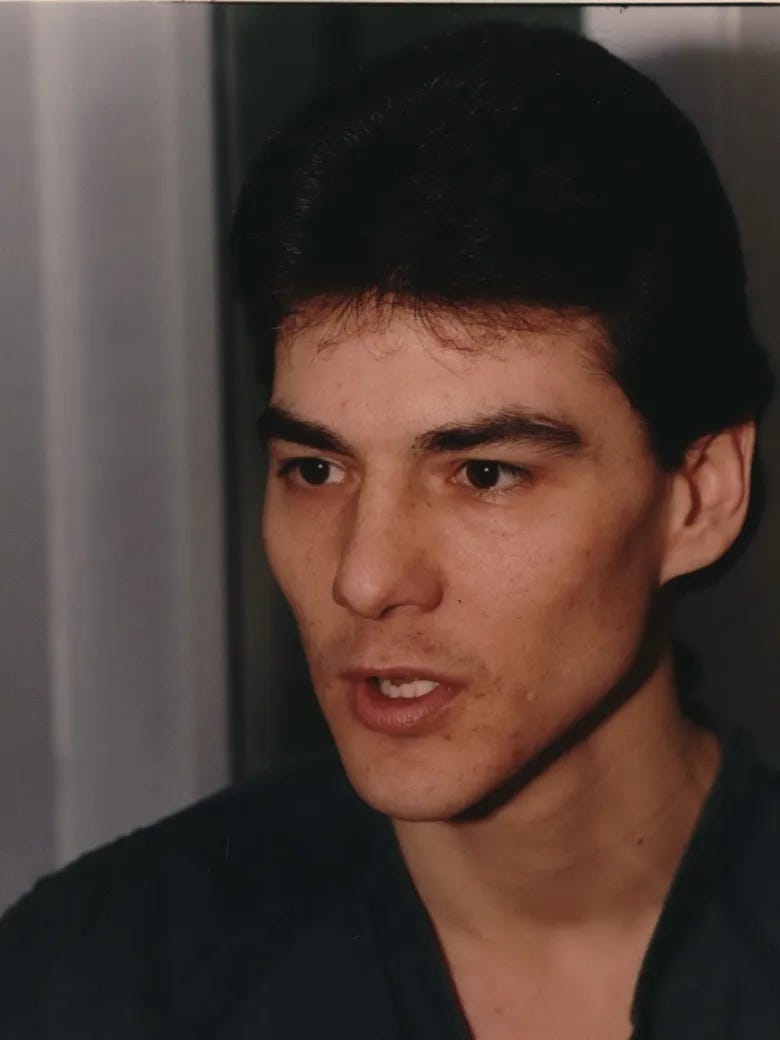

Poor Indian kid from South Dakota. Mother and father both alcoholics. When his father dies, the mother gives him and his brothers up for adoption to a foster parent in Coos Bay on the Oregon coast – where of course he falls in with the wrong crowd and robs a convenience store. No weapon involved, the report says. The friend, also arrested, just held the clerk down while Gable grabbed the money.

After four years in the state pen, Gable’s out now. Twenty-nine years old, living in Salem, married to a woman named Janyne who’s also hooked on drugs, making ends meets by selling meth or whatever else he can scrounge up to other tweakers like himself. Life’s just a bowl of cherries.

Some thirty years later, the set-up is still a puzzle. The official explanation is that Gable came to the Task Force’s attention via a tip about a clearly non-incriminating letter Gable had sent to an old friend in prison, bragging how well he was doing on the outside.

To sweet!! [smiley face]

So are you surprised to hear from the “kid” or not?? Thought you would be. (smile) Anyway, I’m doing super. Things are fine as aged wine out here. I got married about a month ago now. work is also going great also!!! busy as hell. I work at a lumber company here in Salem. I’ve been doing some mellow partying!! the kind that don’t get you into trouble!! ha! had enough of OSP that’s for sure!!!

And so on, just like that.

Somehow, though, the Task Force, which is really floundering a this point, finds it interesting enough that they send a couple of cops over to interview Gable. Gable tells them he doesn’t know anything about the Francke murder and that seems to be it. But it isn’t.

From Salem, the Gables move to Coos Bay where Frank borrows his stepfather’s car for a weekend trip to Salem. When he fails to return on the appointed day, the Francke Task Force puts out an APB (All Points Bulletin), if you can believe that, to arrest Frank Gable for stealing his foster father’s car.

Two days later, Gable is arrested in Salem on the UUMV warrant. Ken Pecyna – who seems to be the lead investigator now – leaves word to be notified of the arrest, no matter what time it occurs. The records shows that he’s called out at 3:30 a.m.

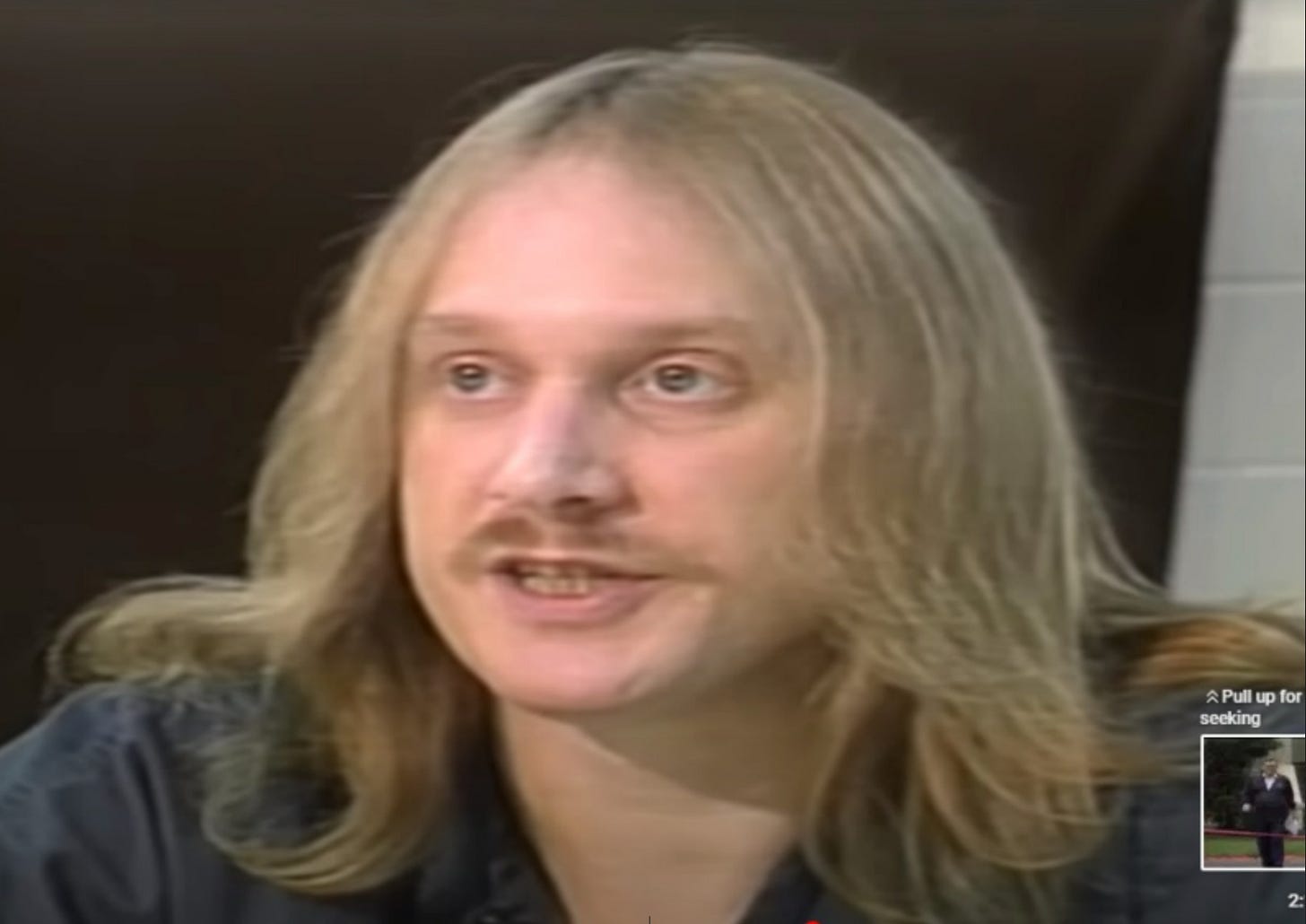

Gable is thrown in the Marion County jail and placed in a cell with a fellow tweaker named Mike Keerins, who several months later will tell police that while they were locked up together Gable told him he killed Michael Francke.

As Keerins will later admit, he was just making it up because the cops wanted him to. And besides, as he would also say, Gable was a snitch – and there’s anything druggies like Keerins hate it’s a snitch. Especially since just about every one of them does it at one time or another. And come to think of it, Keerins is at this moment snitching, however falsely, on Gable.

But if Gable wasn’t a snitch when he went into the Marion County jail, he sure is when he comes out.

While Gable is locked up in the Marion County jail, he’s visited by Keizer police officers who persuade him that the best thing for him would be to play the narcotics game the way it’s supposed to be played.

And how, you may be wondering, does the tiny town of Keizer, which is adjacent to Salem, manage to find its way into this already quite tangled story?

Well, Keizer also has a tiny police force that works hand-in-glove with the Salem and state police, especially on matters of narcotics enforcement. And by way of further explanation, they are of course involved with their sister organizations in the time-honored narcotics enforcement snitch game, which goes like this:

Since both parties to a drug deal are obviously willing participants, the only way to get any information at all about what’s going on is for the cops to team up with one group of drug dealers and get them to snitch off their rivals – in exchange for which they are given a more-or-less free pass.

And sometimes it even works out the way it’s supposed to. The cops get a few busts, and although just about everyone admits it doesn’t really keep any illegal drugs off the streets, you might be able to make an argument that it’s better than nothing at all.

Unfortunately, however, because it blurs the distinction between the good guys and the bad guys, all too often it also leads to cynicism and from there to moral and legal corruption. Sometimes the narcs put the drugs they’ve confiscated back on the streets and become drug dealers themselves. And all too often the protected drug dealers are from time to time expected to express their gratitude by rewarding their friends in the law enforcement community with monetary gifts.

Which, as it happens, is exactly what’s going on between the Keizer police force and the local gaggle of meth dealers known, almost humorously it seems, to themselves and the law as the Keizer mafia.

As Vince Taylor, who was then a member-in-good standing of the Keizer mafia, will later tell me, “Sure, we paid off the cops. Every once in a while they’d pull us over and ask us for $500 or $1000. Of course we did it. We all went to the same high school.”

And as should be noted here, if only in passing, Vince’s boyhood friend and fellow Keizer mafia member was none other than Tim Natividad, who in the last episode of this story, tried to solicit an inmate, Konrad Garcia, to kill Michael Francke.

But for now the question is how Gable, who’s facing prosecution for the unauthorized use of a motor vehicle, plus a charge of felon in possession for a gun that was found in the car, responds to these overtures by the Keizer cops.

And of course he says yes. In fact, as the Keizer police report shows, he even has a few suggestions for how he might be able to prove his worth by gathering information on a lawyer named Paul Ferder who Gable says is engaged in buying and selling drugs with his clients.

Naturally, Gable has no proof of this. It’s just what he’s heard, and there’s no record that Ferder has ever been charged or convicted of anything illegal. However, the fact is that Ferder does represent a number of the so-called Keizer mafia and, as we shall see, it may have been a big mistake for Gable to have brought up his name in this manner.

In any case, an agreement is reached, and in exchange for the promise of a couple of months free rent, Gable agrees to become a snitch for the Keizer police.

As his control officer Kent Barker will later note, Gable never really does much of value – just a couple of $25 buys. But that’s not the point. Gable has now become a snitch for Keizer narcotics – a fact that will soon be bandied about by investigators seeking to persuade other members of the Salem drug underworld to testify against him.

A couple of months later, the Gables, who are now living in Coos Bay, get into another fight. As Janyne will later explain, they often got into fights when they were loaded. Gable throws a plate at her. The plate breaks, Janyne goes to hospital to get stitches in her leg, and Gable is arrested for assault.

The state cops, with Gable now firmly in their sights, come to Coos Bay and give Gable two polygraphs. Gable, who understands exactly what’s going on, complains that he’s being railroaded and that he doesn’t know anything about Francke murder. The polygraph operator says he failed the test.

Two days later, when another state police polygrapher gives Gable the second test, Gable breaks down crying. “I don’t know why you don’t believe me,” he says. The second operator says he failed that one too.

As we know now, Gable was telling the truth. He wasn’t at the scene of the crime and he wasn’t in any way involved in the murder of Michael Francke. As the federal public defender will establish, although unfortunately for Gable many years later, he was home with his wife and a few business associates doing a drug deal.

What’s necessary to keep in mind, though, is that this is not really an investigation. It’s a railroad job. As two federal courts have made quite clear, throughout this entire process the state police will use polygraphs exams such as these to shape and fabricate evidence – and that’s what’s going on here.

The prosecution immediately puts out the word to the same ever-reliable reporter at the Oregonian that Gable is a suspect and has failed two lie detector tests. The Oregonian announces that Gable is the new focus of the Francke investigation, reporting the ominous sounding news that the authorities have been collecting articles of Gable’s clothing from his mother-in-law’s house in Salem (they don’t find anything incriminating), and of course describing Gable as a police snitch.

It's about the same time that Mike Keerins, who by now has been transferred to an Idaho prison, goes public with his claim that while he and Gable were locked up together in Marion County, Gable told him he killed Francke. By this time he's even referring to himself as the state’s “million dollar baby” because he thinks this will put him in line for movie and book deals.

Of course, as Keerins will soon admit, it’s all a lie. He is, in fact, so completely unbelievable that the prosecution won’t even use him as a witness when the case finally comes to trial.

But by then it won’t make any difference. Gable is well on his way to being framed.

Back in Florida Kevin is pursuing his long distance investigation, running up huge phone bills just trying to find out who the players are. The Keizer mafia comes up, and one of the rumors he hears is that a young gangster named Tim Natividad, who’s part of it, is somehow involved in his brother’s murder.

But then it really gets crazy. Just two weeks after the murder, Natividad himself is shot and killed by his girlfriend – who, the rumor goes, was probably being paid to do so by a larger drug syndicate to keep Natividad from talking.

Of course, Kevin doesn’t know yet about Natividad’s efforts to enlist an inmate, Konrad Garcia, to kill Francke. And although the drawing of the Man in the Pinstripe Suit has been released by now, he’s unaware, and will be for some time, that anyone thinks it might resemble Natividad.

However, he is still quite interested, even if the Francke Task Force doesn’t seem to be, in finding out who the Man in the Pinstripe Suit is, if only because he was seen inside the Dome Building after closing time on the night of the murder.

But when he finally gets to talk to Dennis O’Donnell, the former narcotics agent who’s now running the state police investigation, O’Donnell assures him it’s just a copy repairman who was doing business in the Dome Building that day.

I track down the copy repairman, a mild-manner fellow named Dennis Plant who lives in suburban Washington, and he turns out to look nothing like the well-groomed, olive-skinned man seen in the Dome Building that night. He has sort of reddish hair, a pale northern European complexion, and says he was wearing a brown tweed jacket that day. He doesn’t even own a pinstripe suit.

Yet even after O’Donnell is confronted with side-by-side photos of them, he continues to insist that’s who the Man in the Pinstripe Suit is.

For Kevin this is the last straw, and he tells O’Donnell so when he and brother Pat are in Salem again.

As he also tells O’Donnell, he doesn’t think the man Hunsaker saw turn and walk back toward the Dome Building shortly after 7 p.m. on the night of the murder was Michael Francke, either. Which would mean that more than one person had to be involved in the murder.

“Someone who’s just been stabbed in the heart, walking like he doesn’t have a care in the world? Gimme a break, Dennis.”

“Well, Kevin,” says O’Donnell, “it is what it is.”

Then turning to Pat, O’Donnell says, “Hey, Pat, think you could maybe get your little brother to screw his head on a little tighter?”

And for Kevin, who’s already been called crazy for saying his brother was investigating corruption, this just about rips it.